(The following article is mostly from Sounding for Harry Smith: Early Pacific Northwest Influences)

This is the month Harry Smith turns 100. Wherever you are, get ready to spin some records for the party on May 29th.

It goes all the way back. Harry shared the history of his Northwest roots: “Before I got interested in record collecting, I got interested in Indians....this was in Anacortes, Washington, on an island...my grandparents were there when there were hardly any white people.”

Young Harry Smith, living in an empty salmon cannery located in the homeland of the Samish Indian Nation, was inspired to start his own “museum” for his many collections. His special talents for assessment, acquisition, integration, and creative action were famously brought to life when he turned his collection of thrift store records into the enduringly influential Anthology of American Folk Music.

Harry Smith may be best known for his folk compilation, but his Anthology collaborator, Moses Asch, the founder of Folkways Records, echoed Harry: “Actually his interest was originally in the American Indians of the Northwest. That’s how he became interested in music as such and he documented very early.”

He was beginning to collect old phonograph records as a teen; he’d also begun to make recordings as part of his studies. This interplay of recording and collecting cannot be underestimated in the magic of the Anthology. Both of these early 1940s pursuits were happening in the same time period, not strictly as sequential phases. Though intertwined, it is useful to consider the development of each individually.

RECORDING

Harry’s creative interests were nurtured by his parents. “My earliest recordings were made about 1942 – they were children’s songs sung by my mother,” Harry wrote. It may have been earlier, because Harry’s classmate Jack Wells remembered collaborating with him before the war:

“One thing that is clear, he and I drove over to one of the potlatch celebrations near La Conner—Swinomish Indians. And we had rigged up an inverter to operate off of a battery to power a fairly conventional disc recorder—we didn’t have wire recorders at that time—with moderate success.

I think it was a mutual interest where I was willing to help him out because he was in need of support on the electrical side of it. I think that we’d gotten some kind of clearance from the Indians. One thing I remember is smoke getting in our eyes ... they had the fire raging ... the smoke would go up through the hole in the potlatch building. And of course there was the chanting and the dancing around the circle and so forth. And that’s what Harry wanted to record. He wanted not only music but the chanting of the words .... What the chants were supposed to be imputing.”

Jack’s mother may have connected Harry Smith to events on the Swinomish Reservation, he said, “that may have preceded my going with Harry, because I didn’t feel as uneasy when I went with him.” Verna Wells operated a music studio for her classes in one of the family’s Commercial Avenue buildings. She also published sheet music, and one of her songs, “Darling I Miss You So,” was recorded and released on the Morrison label, a company whose owners had Anacortes roots.

Bill Holm, who around 1942 teamed up with Harry, recalled: “The teenage Harry Smith, at that time, as a young boy already an ethnographer, and a very good one. He was really interested in languages and did some wonderful work, linguistic work. Most of which is lost. And we don’t really know what happened to his records at all. Very few parts of it have been preserved.”

Although Harry had dropped out of Anacortes High School entirely by the spring of 1942, he remained engaged in his many other interests. In his correspondence with Bill Holm in February, addressed from Apex Cannery, Harry invited his friend to join him at “Clean Up Day” on “next Saturday, the fourteenth, at the Smoke-house on the Swinamish [sic] Reservation.”

Robert, Mary Louise and Harry Smith left their cannery row home at the Apex and moved back to Fairhaven. Bill Holm remembered teaming up with Harry for more recording projects:

“In the summer of 1942 I was working on a camp in the San Juan Islands. I took the mail boat to Bellingham, and went out to visit Harry, and we went out to the reservation. And these are the kind of equipment pieces that we used, and Harry put together pretty much on his own invention. He had car batteries, a transformer, a recorder that cut the grooves in the round black disc as you went. And you had to keep sweeping the cuttings off the disc so they didn’t foul up the needle. We had a lot of experiences and adventures with that.”

“Nowadays, and since the Second World War, it is not possible to record things in the smokehouse. So “Wey7qe7”—Harry Smith— could bring his recording equipment right into the smokehouse and we had some interesting experiences. The drums come out very loud. The singing is hard to hear. Well, we never really knew if we got anything on the recording. So in between dances, when there was a lull in the performance, we would crouch over the machine and put a blanket over us and turn it up so we could barely hear it.

Toward the end of one of these experiences a man came to Harry and he said, “did you record that woman’s song?” And Harry said no. He said I didn’t have permission to record it. We always got permission from the people to record their songs, because they were personal and powerful things.”

About two months before Harry turned twenty, the first instance of his national renown rippled back to Anacortes, translated in the Anacortes American, March 11, 1943: “The American Magazine for March has an interesting article about Harry Smith, a former Anacortes lad, son of Mr. & Mrs. Robert Smith of South Bellingham.”

“Harry is quite interested in anthropology and has taken hundreds of photographs, made records of tribal music on a portable recording machine, and is compiling a dictionary of several complicated Puget Sound tribal dialects. In the picture in the magazine he is shown recording the drums and chants of the spirit dance at the Lummi annual potlatch, and pictures of Chief August Martin, Jimmy Morrice and Patrick George are also shown in tribal costume. Harry expects to go to the University of Washington, where he will continue his studies on anthropology.”

Harry continued his recording projects at university. Harry told P. Adams Sitney: “I made a very large number of recordings that were also unfortunately lost. It’s remarkable music. I took portable equipment all over that place long before anyone else did and recorded whole long ceremonies sometimes lasting several days.”

COLLECTING

What kind of music did the Smith family listen to at home, assuming they had a radio or phonograph? “There was a certain type of music that everyone was exposed to in the 1920s: the Charleston, Blackbottom, etc. The babysitters I had were doing those things. I was carried along,” Harry recalled.

For as long as Harry was in school, phonograph records were sought for education - but only the right kind of records were requested in Anacortes: “We must have a circulating library of records which can go from school to school and give every child in the city a chance to hear the best of the world's music, lessons in appreciation will be given with the music. No jazz records will be used, and it will, of course, be useless to send cracked or broken ones.”

Harry’s own mother used art and music when she worked as a teacher in Native Alaskan communities before Harry’s birth. A magazine article recounted her time there: “Music, however, is the thing that wins them, from the old, gray haired men and women to the little boys and girls. They love music. There is not a popular air that has been sung in the United States in the last 10 years that is not common in Afognak within three months after the record is made.”

About 1940, Jack Wells and Harry were chumming around, consigned to the Anacortes High School bleachers in P.E. class, and talking about both records and recording projects. Jack recalled, “Harry and I both liked classical music and he came upon a deal where we could get two 12” RCA Victor Red Seal records for I think it was only about $2 and a half.” Locally, Jack recalled, “records were purchased at the DeRemer’s music store.”

According to Harry,“the first records I bought were in Bellingham when I was in high school around 1940. It was a Tommy McClellan record that had somehow got into this town by mistake. It sounded strange and I looked for others and found Memphis Minnie.” Harry said: “I started looking in other towns and found Yank Rachell records in Mt. Vernon, Washington. Then, during the record drive—I then arranged for other people to look for old records. People collected records because you could sell them for scrap.”

With the entry of the United States in World War Two, people were asked to conserve and recycle the shellac in phonograph records so that it could be used for military purposes; this also served to stir up the whole country’s music collection.

Early in 1942, nationally known musicians teamed up with the American Legion in widespread community record drives meant to supply “Records For Our Fighting Men.” at local canteens and overseas posts. Meanwhile, new record production was slashed by 70%. Old, even broken records were requested to augment the shellac supply. “Boxes to receive your contributions have been placed in the following business places: Penney's Store, Post office, Allan’s So. Side Market, Murdock’s Barber Shop,” the Anacortes American reported.

Imagine teenage Harry Smith, going about his usual business in Anacortes and, then Bellingham, but now everyplace had a box of varied records to snoop through.

In his youth, Harry found his way to far-flung reservations and record stores across the Northwest. “Harry was both intuitive and scholarly in his approach to collecting,” according to Chuck Pirtle. “He said of his first blues record, ‘It sounded strange and I looked for others.’” Chuck continued:

“Harry’s interest in folk music pretty much proceeded from the same sources as his interest in ethnography. And what interested him, maybe what’s the basis for all of his art and scholarship, really is just the rich vastness of the variety of different ways of being human that there are in so many different places on this earth, and expressing what it is to be human.”

ANTHOLOGY MAGIC

Free spirits resonate—attract attention—compel the distribution of myths. Whether relay race or weird parade, we pass on meaningful messages. What misfit power might we discover—straw spun to gold—by considering the boyhood community of a man who claimed, as he accepted his 1991 Grammy, the Chairman’s Merit Award for Lifetime Achievement: “I’m glad to say that my dreams came true—I saw America changed through music.”

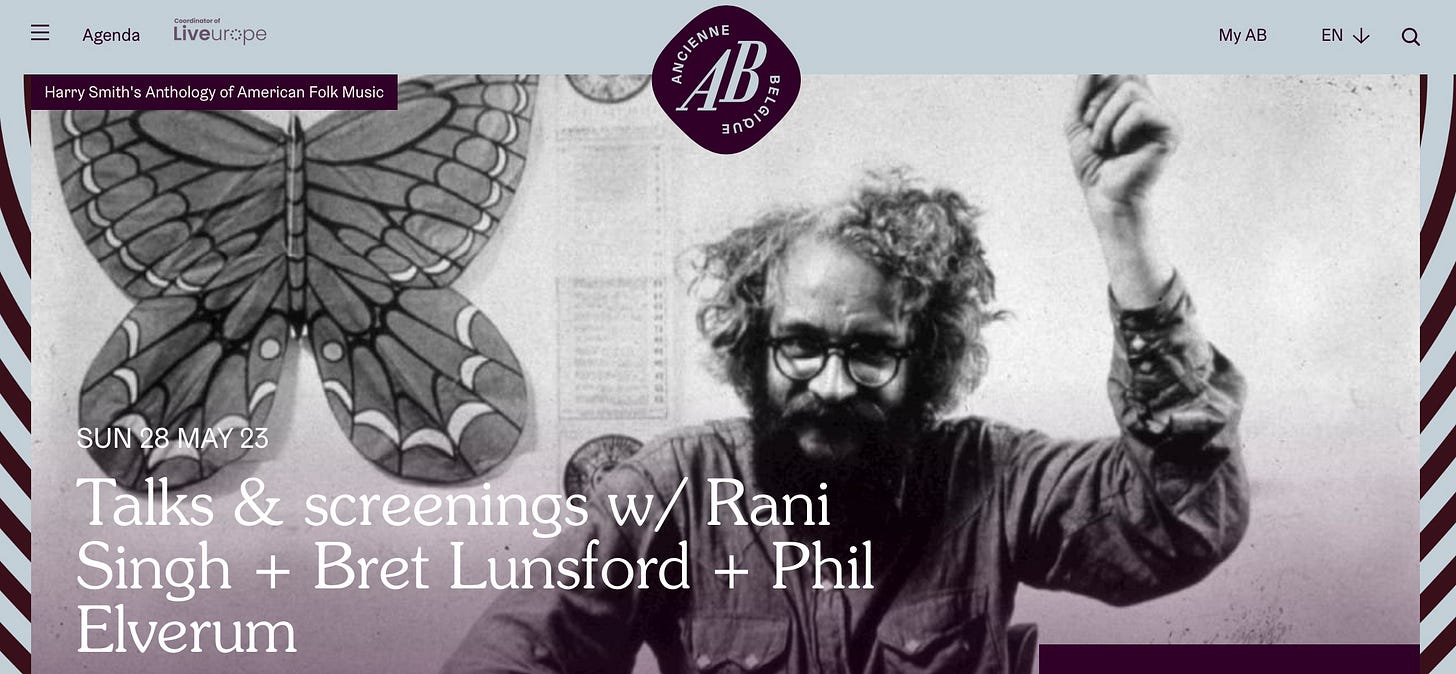

A confluence of songs and languages blossomed on Anacortes streets and wharves early in the 20th century. Swimming against the current of mid-century conformity, Harry Smith dove in to rescue holy grail folk records from the recycling bins of World War II. Harry’s anthology was described by Allen Ginsberg as “a historic bomb in the American folk music” - exploding the era’s WASPy ideas defining “the best of the world’s music.”

Here is where the teenage ethnographer went deeper. Not just finding rare old 78s, but recording what was rarer still. In becoming Harry Smith, he listened and learned from the Coast Salish people - Charlie Edwards and Amelia Billy and Julius Charles - whose culture stretched from time immemorial to the present day. His work to record and transcribe the musical patterns of dance ceremonies at Swinomish and Lummi reservations changed Harry’s methodology and his mindset, and his approach to his creative life.

As the age of progress succumbed to mid-century monoculture, Harry’s pursuit of uniquely common voices and underlying patterns of traditional ways is profound, exceptional. Neither jaded nor naive, Smith remained in lifelong contact with the passions of his youth. His childhood games became studies: self-exploration with societal implications. Granted a room of his own while still in the nest, Harry became proprietor and pupil at his own DIY daycare. Here he developed strength of vision and a resourceful belief in his purpose.

According to Harry:

“It’s better to have people singing, and get more people singing than to have more radios, as far as music is concerned ... it’s more important that some kind of pleasure can be derived from things that are around them. I now believe that the dissemination of music affects the quality. As you increase the critical audience of any music, the level goes up.”

We may presume by Harry’s inclusive cultural values that he learned some of this from his parents’ spiritual and societal beliefs. “(Harry had) this utter respect for every culture and society in the world and the feeling that no one culture was superior to any other,” Joe Gross recalls Harry saying. He believed “that each culture had its own genius ...was a manifestation of God in some way.”

This principle of humanism may not have always been a part of Harry Smith’s interpersonal practice, but it was applied to many of his anthropological projects. In his 1952 introduction to the Anthology of American Folk Music, Harry wrote:

“Only through recordings is it possible to learn of those developments that have been so characteristic of American music. Records of the type found in the present set played a large part in stimulating these historic changes by making easily available to each other the rhythmically and verbally specialized musics of groups living in mutual social and cultural isolation.”

Some of the isolation was due to musical market barriers. Harry quoted Ralph Peer, the inventor of the “hillbilly records” and “race records” terms: “We had records by all foreign groups: German records, Swedish records, Polish records, but were afraid to advertise negro records, so I listed them as ‘race records’ and they are still known as that.”

The Anthology was groundbreaking for throwing race out the window as a categorization method, at a time when “race music”—which Harry considered an “unpleasant term”—was used to segregate markets, and hits made by African American artists were rarely allowed to cross over to the mainstream. Instead, on Harry’s anthology, “the first criterion was excellence of performance, combined with excellence of words.”

What kind of voices can be heard? This story follows a version of Harry Smith who digs for the understanding way. He learns from, records, and amplifies the voices of others, an advocate for unique beauties. Among Harry’s varied brilliances, it was his ability to listen and see and value and act in concert with the preservation of cultural treasures—those that surface forces had lost, or tried to break and bury. In the mountains of scrapped 78 rpm records, Harry heard the patterns in disparate compositions as a choir compiled to sing a new American folk into existence. In a sense he fulfilled with the Anthology his high school yearbook ambition – to be a “composer of symphonic music.”