(I met Mr. Jones at a book tour event I hosted for John Szwed’s Cosmic Scholar at the Anacortes Public Library. Jim told a short version of this story during the Q&A. I asked if he would write it up … and here it is. - Bret Lunsford, author of Sounding for Harry Smith and publisher of this Resounding substack)

When I went to the Naropa Institute in the summer of 1988, I had never heard of Harry Smith, despite having been a folk musician all my adult life. But I immediately perceived that there was a buzz on campus about this grizzled old guy. He had just given an outdoor lecture on folk songs that had been composed for use as state advertising jingles, and some of the undergraduates reported semi-mystical experiences at his talk, several people hearing him say different things at the same time. They were also impressed that Harry smoked marijuana as he delivered his lecture.

My main job that summer was to drive Allen Ginsberg to his many appointments in and around Boulder, a job that I shared with Steve Creson, who subsequently edited and published the first book about Harry, Think of the Self Speaking. On my days off, while Steve was looking after Allen, it sometimes fell to me to look after Harry. His attitude toward me, an academic, was wry, to put it mildly. His voice was raspy, so when he spoke it was like listening to the whine of a small power tool that was running out of juice. He was not a physically attractive person at that point in his life, either. Though he was just sixty-five, he looked like he was ninety, and his frazzled beard was usually clotted with milk or other things he had regurgitated. But though he looked unwell, his mind was as sharp as his voice.

At some point, Allen introduced me to Harry, explaining that he had brought him to Boulder to get away from the temptations of New York City, by which he meant mainly amphetamines. Allen also brought many of his other friends and associates to Boulder in the summer for a paid vacation, so I met William Burroughs, Gregory Corso, Marianne Faithfull, Francesco Clemente, the Islamist and anarchist Peter Lamborn Wilson, Peter Rowan, and Steven Taylor (of The Fugs, Allen’s guitar accompanist) at the same time I met Harry. I suppose he thought the mountain air and the spiritual atmosphere of Naropa would do them good, and I imagine it did. It certainly is an invigorating place to spend the summer. But you could tell Harry was in bad shape. He could eat only soft food, and even that he had trouble keeping down.

I happened to mention to Harry that another older student at Naropa that summer had been raised by a Maori nurse in New Zealand. That piqued his interest, so I arranged for him to meet Laura in my apartment one afternoon. They plunged right into a discussion of Maori folkways, and for a couple of hours she recounted tales her nurse had told her when she was a child, while Harry took notes and asked questions. The anthropologist in him was always near the surface.

Another afternoon remains particularly vivid in my memory. Harry wanted to go shopping, and I was free that day, so he and I and the poet Lee Ann Brown squeezed into the cab of my Mazda pickup truck, and drove downtown to the Boulder Book Store. Harry was always in search of reference books on any subject, as well as technical instruction manuals and collections of music. In fact, that same day he asked me if there was a Baptist church in Boulder where we could pick up a hymnal. Well, Lee Ann went with him into the bookstore to carry his purchases, while I sat in the truck in the shade.

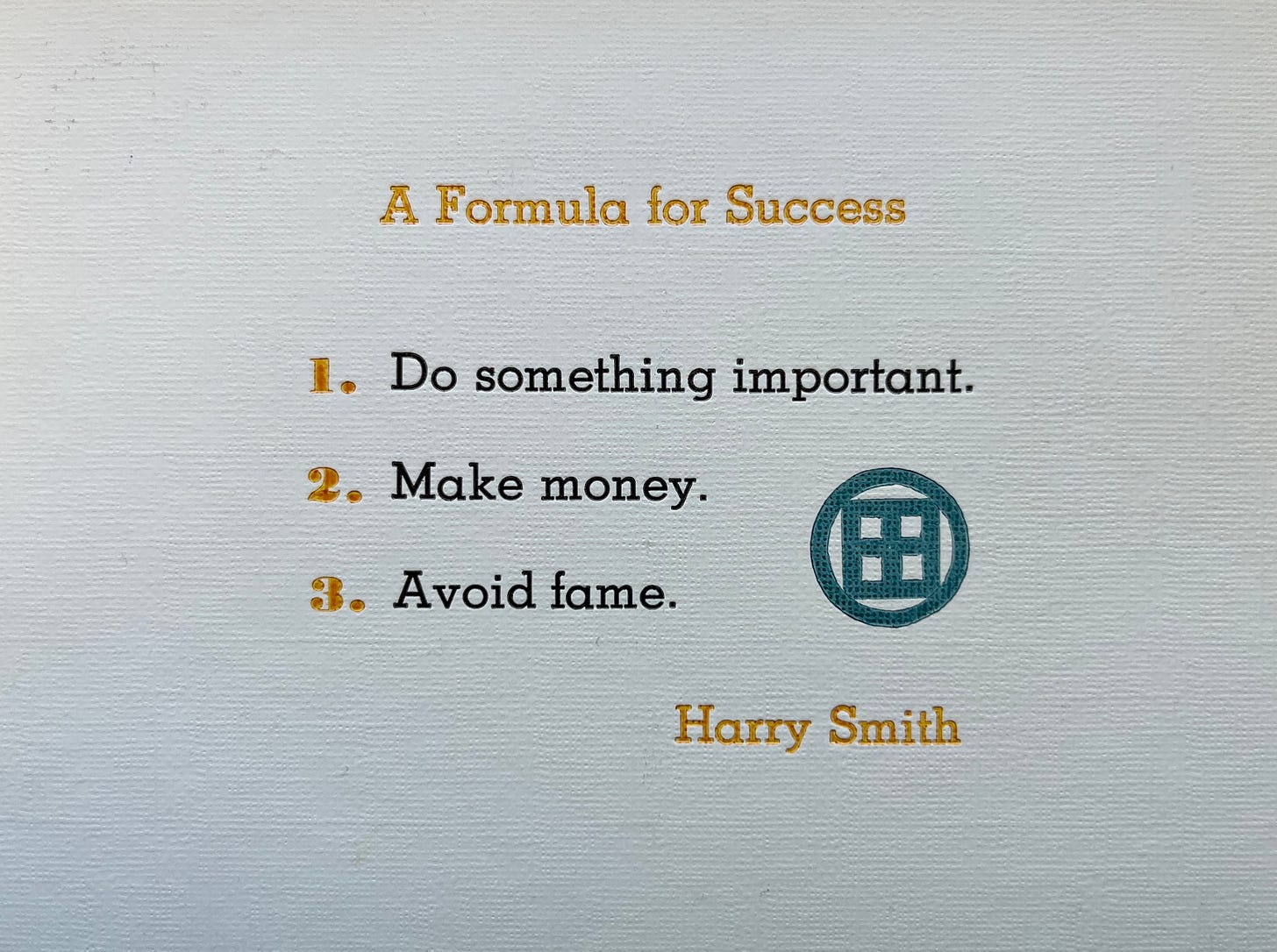

I noticed that Harry had left a plain manila spiral notebook on the dashboard, and without even thinking, I picked it up and started to leaf through the pages. There were lots of scribbled notes and some diagrams, but one page in particular caught my attention. So much so that I copied Harry’s words into my own pocket journal. There were only three numbered lines: 1. Do something important. 2. Make money. 3. Avoid fame. Twenty-some years later, after I had learned to be a letterpress printer, I designed and printed a postcard with this list under the heading “A Formula for Success.” I thought it was a good message, if not a code to live by.

Harry Smith actually did important things in a range of fields, and although he never made much money, he managed to fund his many projects, including rather expensive ones like filmmaking. And as my own ignorance of his existence before the summer of 1988 testifies, he certainly never became a household word. That seems to be changing now. The influence of The Anthology of American Folk Music is widely acknowledged and celebrated. His experimental movies have taken their rightful place in the history of avant garde film. The eminent biographer John Szwed has released the first full-length account of Harry’s life. And thanks to Bret Lunsford, the influence of the culture of Anacortes, Washington, Harry’s hometown, has also been detailed in a book. It’s been over thirty years since his brush with fame in the form of a Grammy Award, but Harry Smith’s legacy is finally being recognized. And judging from the last item in those notes I saw in Boulder in the summer of 1988, it’s entirely fitting that this recognition comes posthumously.