“There’s a misfit in this town”

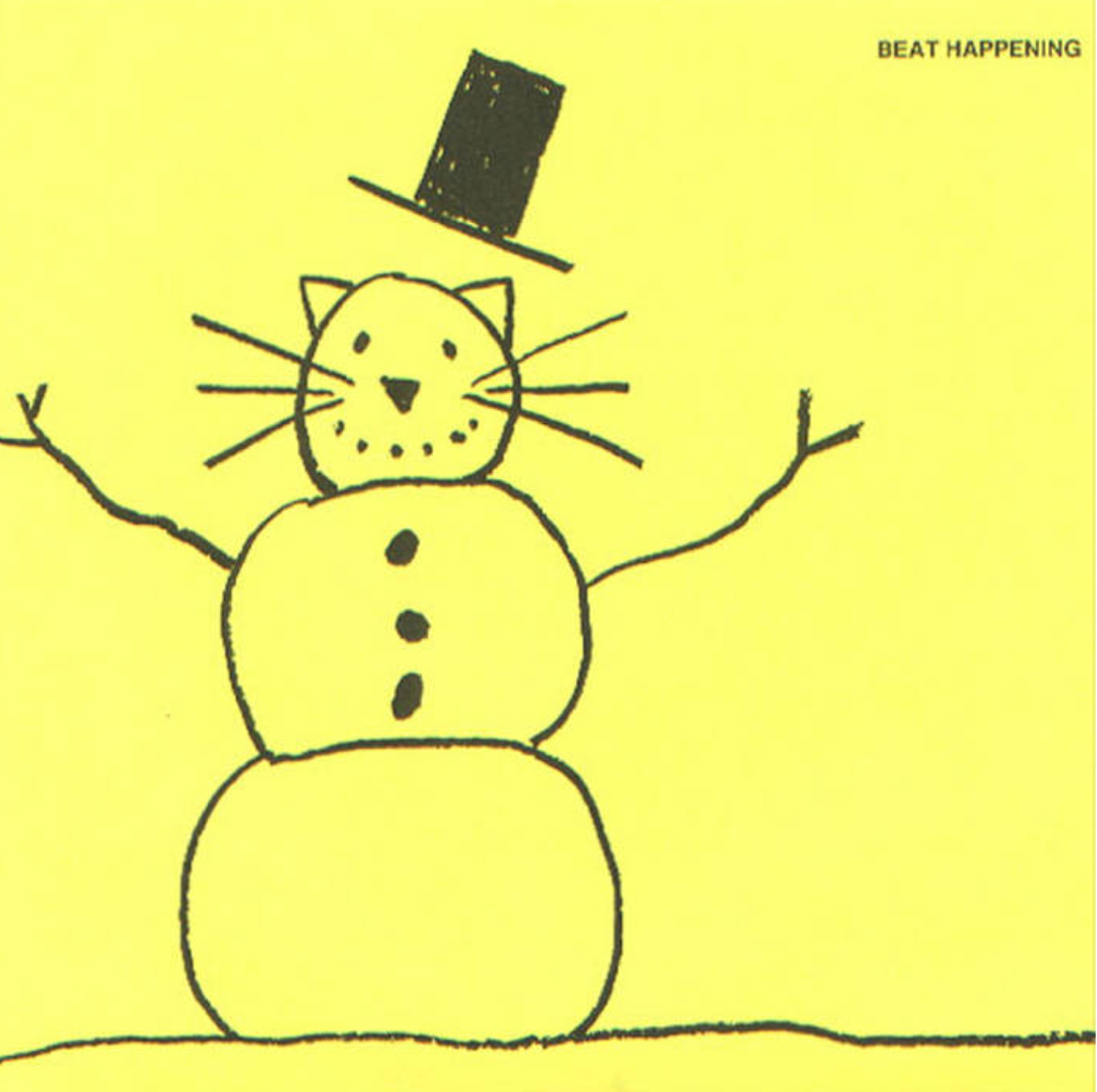

I was asked to prepare for two different podcasts, one about Burl Ives and his Christmas gift to Anacortes, and the other on Beat Happening in the 1980s. Naturally, my mind being the center of my universe, I began scripting a podcast that bridged the subjects (stretching further still to Harry Smith). Okay, that’s what podcasts often do: throw random ideas in a hat, then compare and contrast.

Remember televisions having only a few snowy channels? And those footsteps on the roof weren’t Santa, but someone turning the antenna while reception instructions were yelled out the window.

Early in my childhood, three holiday classics launched between Thanksgiving 1964 and Christmas 1965 and entered into a close cultural orbit: Santa Claus Conquers the Martians; Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer; and A Charlie Brown Christmas. Each might be interpreted as addressing post-JFK social malaise and invoking Christmas spirit as consolation. Alien, underdog and outcast redemption stories all, these feelings have been folklore floorboards throughout the decades since, still heard even when political pundits misuse “island of misfit toys” as a way of dismissing weirdos.

My horoscope advised research yesterday, so I read up on Rudolph’s history. What began as a seasonal Montgomery-Ward department store give-away book written by Robert May in 1939 was turned into a song by his brother-in-law, Johnny Marks, becoming a hit in 1949 for Gene Autry. Marks and Greenwich Village neighbor, Arthur Rankin, began planning a television program in the early 1960s, bringing in writers Romeo Muller and Tony Peters with Ani-magic visionary Tad Machinaga.

It should be noted that some at Montgomery-Ward had reservations initially about the Rudolph story and were concerned about a red-nosed character maybe symbolizing drunkenness or worse. May, a Jewish widower, kept counsel with his young daughter and held his ground. May later said: “Rudolph and I were something alike. As a child, I’d always be the smallest in the class…I was never asked to join the school teams.”

Marks had interest from Perry Como in his song about Rudolph, but a lyric change request stopped the deal. Autrey’s wife, Ida, sensed that the underdog theme would click. She lobbied Gene, who grudgingly put it on a B-side that turned the tables and went ballistic.

Rudolph connects to Anacortes in the form of cutout plywood mural paintings of characters like Sam the Snowman, Yukon Cornelius, Hermey and the Bumble. These figures were created for and displayed by Burl and Dorothy Ives when they lived in Anacortes in the 1990s, and since 2017 have become a holiday display favorite at the Anacortes Museum. This “Abominable Selfies” exhibit was why Feliks Banel invited me on his Cascade of History live radio show and what caused me to ponder my season’s feelings.

Anacortes can claim two very different folk-rooted, Grammy-winning residents. Allen Ginsberg described Harry Smith as “famous everywhere underground,” but Harry remains largely unknown in his hometown (remedied one book at a time by Knw-yr-own’s Sounding for Harry Smith: Early Pacific Northwest Influences).

Burl was the famous folkie here, retiring to a hero’s welcome in a high-bank cannery row home overlooking Guemes Channel. Yet while Burl’s voice boomed from Hollywood to Billboard throughout the 1950s and 60s, Harry’s Anthology of American Folk Music was kindling a folk revival through libraries and coffeehouses across the country.

It's easy to forget how new television omnipresence was in the 1960s. My mother’s generation was listening to radio shows from Seattle in the 1940s, wirelessly bringing a source of folklore into their homes in Anacortes that the previous generation only dreamed of. Burl Ives could be heard on radio station KVI throughout the decade, introducing his resonant folk style to the Pacific Northwest, where my mom (and Harry Smith) might have tuned in to hear “The Wayfaring Stranger” sing an American songbook that drew upon the research of the Lomax family.

Burl Ives, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Alan Lomax and Harry Smith each played important roles in collecting and sharing folk music traditions in 20th century America. These interests made some the targets of the blacklisting that permeated the entertainment industry during the post-WWII Red Scare. Considered from the red-nosed perspective, reindeer game exclusions align fantastically as abominable McCarthyites villainized New Deal progressives, which led to a life-wrecking House Un-American Activities Committee campaign to destroy and discourage dissidents. Many artists, musicians and actors were not allowed to work, lost performance and recording contracts, unless they named their friends to the witch hunters. While Burl Ives cooperated, his old friend Pete Seeger refused, making this misfit’s statement to the HUAC:

“I have sung for Americans of every political persuasion, and I am proud that I never refuse to sing to an audience, no matter what religion or color of their skin, or situation in life. I have sung in hobo jungles, and I have sung for the Rockefellers, and I am proud that I have never refused to sing for anybody. That is the only answer I can give along that line.”

Seeger ultimately regained access to radio and television as the blacklist thawed; his Rainbow Quest TV show is a mid-sixties counter-culture antidote to consider against the dominant mainstream forces. Try watching a few Rainbow Quest episodes, of Buffy Sainte Marie or Reverend Gary Davis, alternating between Dean Martin or Andy Williams Christmas specials if you want to test your sense of 60s-era contrasts.

Of course, Harry Smith excels in the misfit role. Lionel Ziprin tells a story (in the newly reissued American Magus) about how Harry worked for the Ziprins greeting card company in 1950s New York, painstakingly creating a 3-D Christmas card effect that ultimately failed: “Years later, I finally figured out why it didn’t work. You know Harry is astigmatic; his glasses are so thick. So he wasn’t seeing like ordinary people. Do you understand? He wasn’t seeing like a customer was when he picks up the cards,” Ziprin said.

I watched Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer recently with my grandkids, and I took note that only the misfit toys and trailblazers have personalities in this drama. The others play roles of bullies and bystanders, cliches like Comet the Coach, where the conformists may as well have the “wha wha” voicing of adults in a Charlie Brown special.

The forgotten dream star is King Moonracer! Please can we have a TV special or a new folk song about this winged lion’s nightly flights around the world to rescue the unloved from isolation and neglect, bringing them all back to the island of misfit toys, where at least they have each other.